Pulling at threads and finding infinity

Going down an art rabbit hole, embracing glitches, and accepting the help of AI friends. The first post on a new blog about making art, learning things, new technology, and being human.

Last week I pulled at the thread of an old art project and stumbled into an endless world of unpredictable, captivating patterns.

The creation was inspired by a few pioneering artists from the 60s, went through many unplanned evolutions, a lot of which were executed by AI, and points to the freeing, assistive, and revelatory power of this new technology.

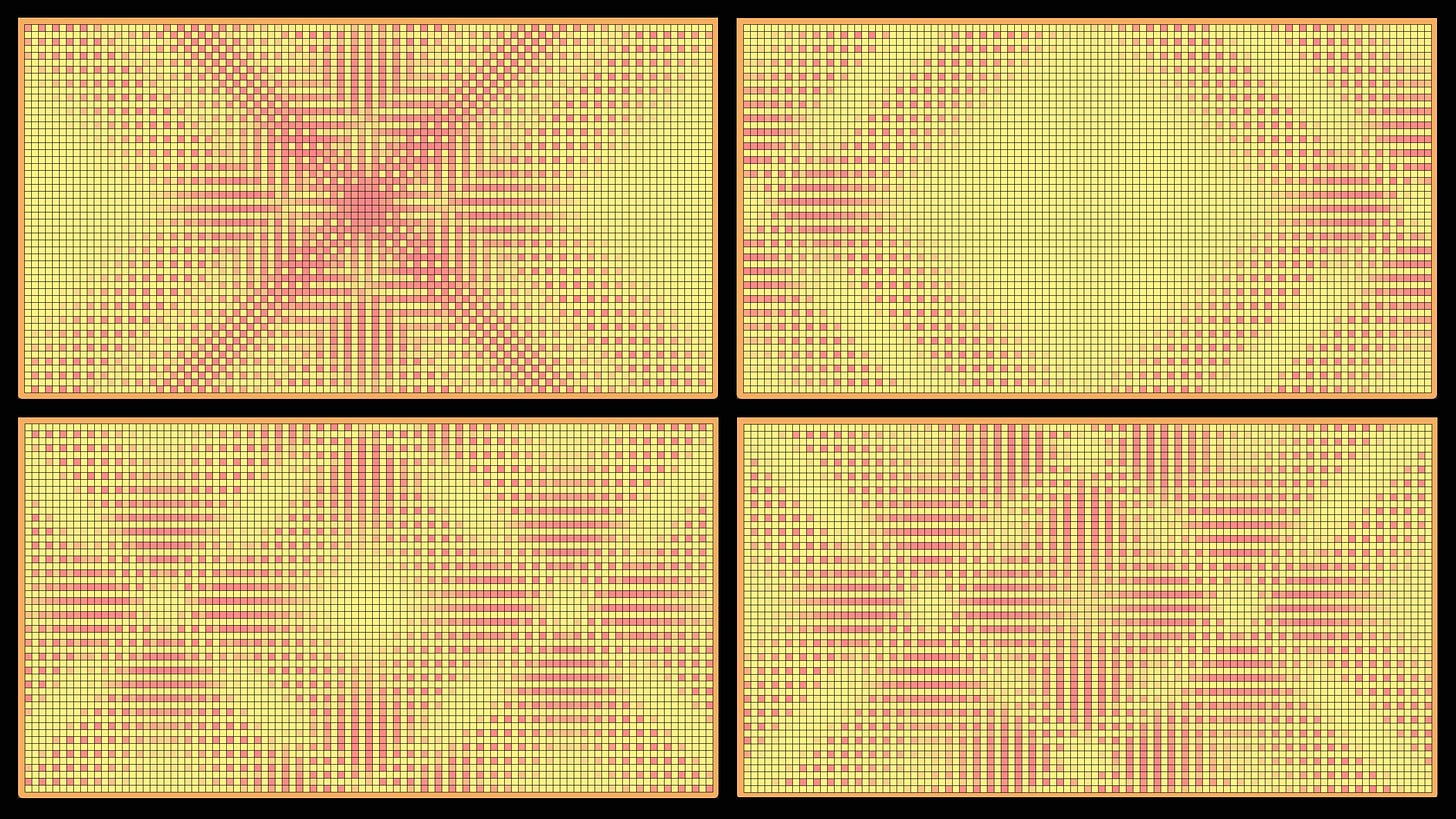

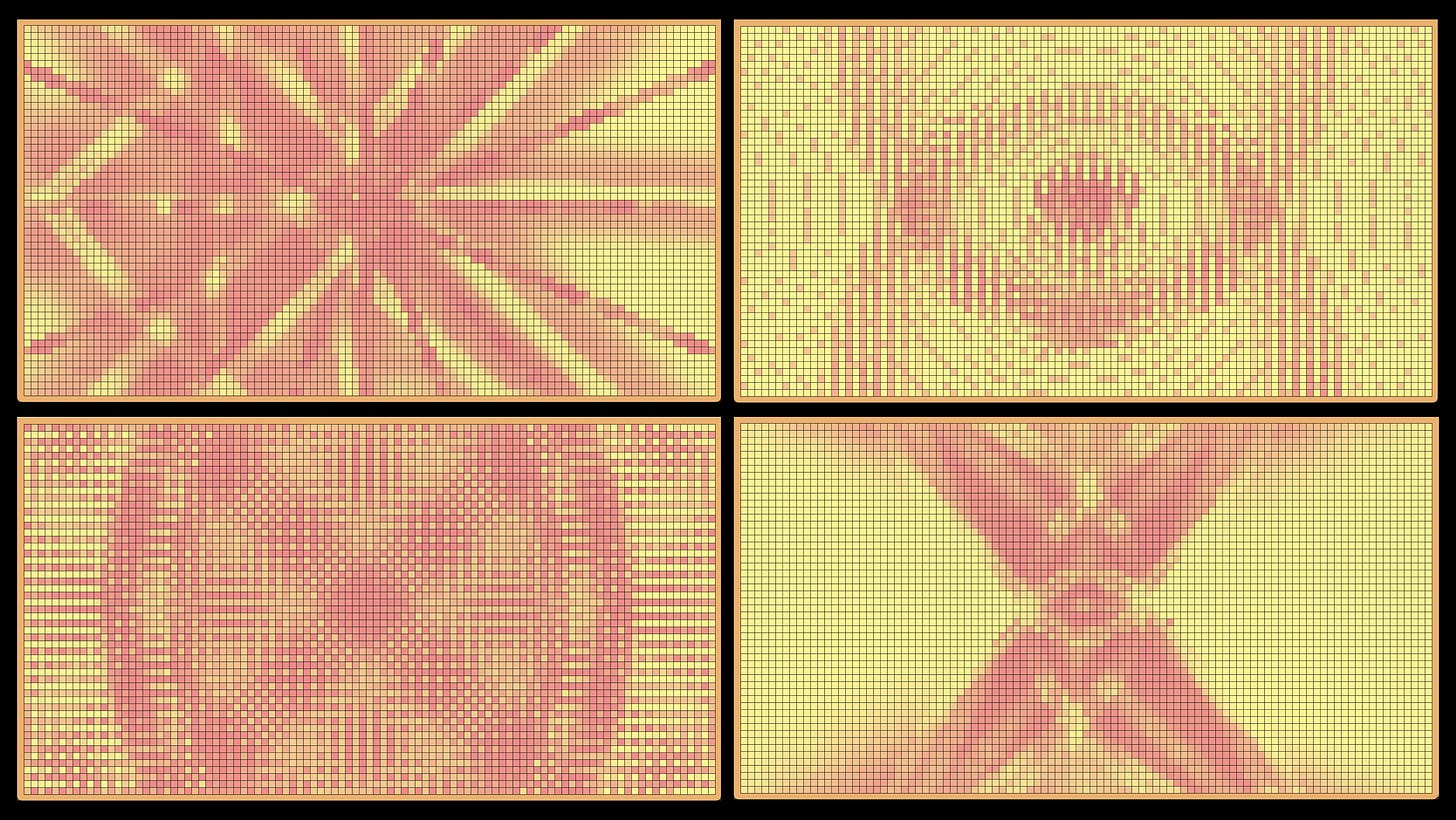

When I first triggered these animations, I had no idea these patterns would emerge.

Eclipses and procedures

The story starts on the day of the Great American Eclipse of 2017. We drove north of New York to catch the totality from the top of a hill, and afterwards we went to a nearby museum, Dia Beacon, to see some of Sol LeWitt’s procedural drawings in their building sized glory.

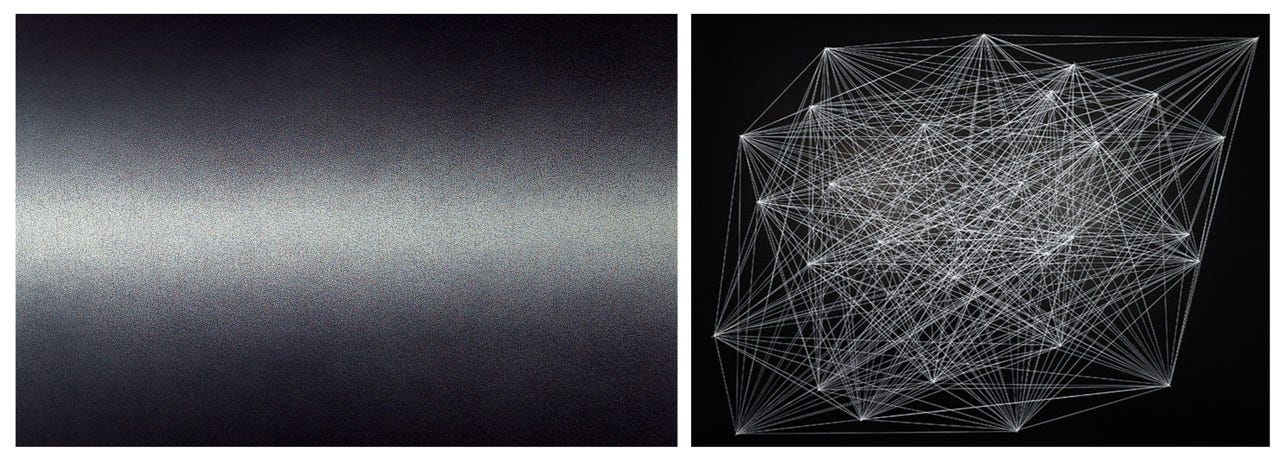

In the late 60s, Sol LeWitt started a series called wall drawings: instructions for artworks written by him but executed by others, drawn on walls without his involvement. Procedural art before computers. He produced thousands of such instructions over 4 decades, my two favorites of which are #1185 (Scribbles: Inverted curve (horizontal))1 and #815 (Thirty randomly placed points connected to one another using nails, white string on a black wall). They feel modern but timeless, human but machine-like, perhaps…cybernetic.

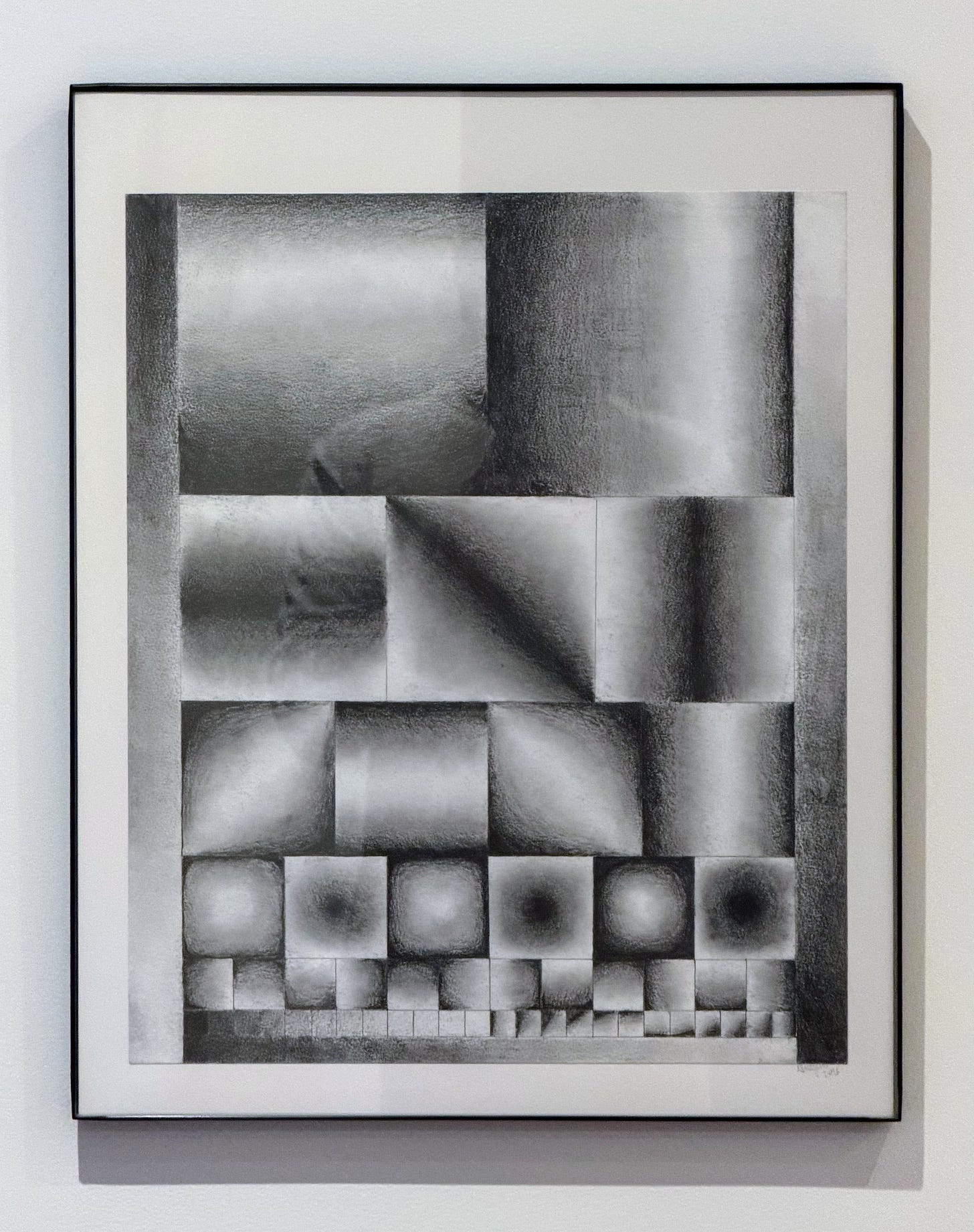

A year earlier, I had been making some procedural drawings of my own: simple rules applied repeatedly, with randomness to create chaos. It was a time of change, and drawing and shading were meditative outlets for a lot of new energy. Four pieces came out of that period that are still up on my wall.

This one is my favorite:

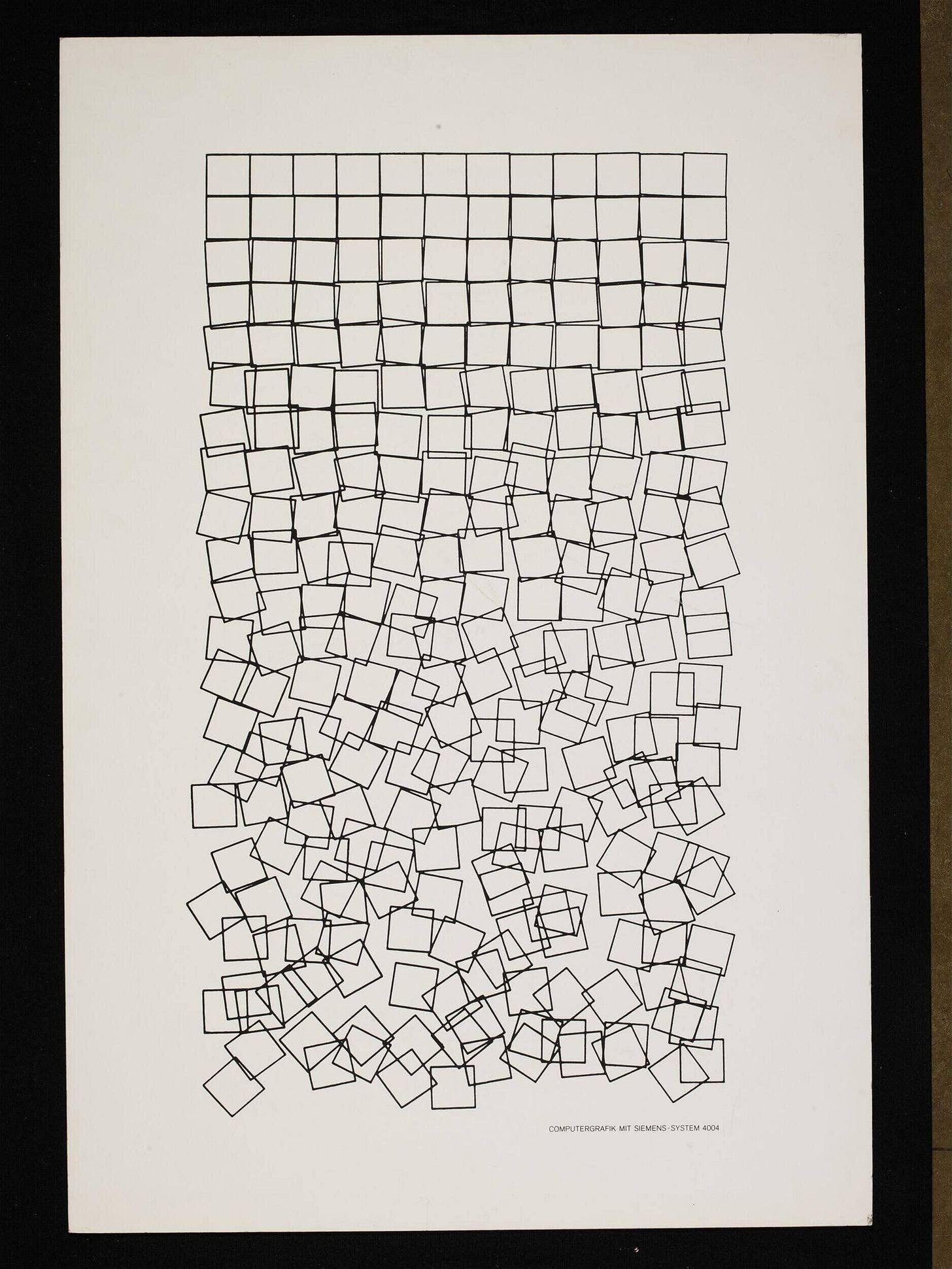

After seeing Sol’s analog ‘programs’ at work, I wondered what early programmatic art was like, and in that search I found Schotter by Georg Nees. Nees was one of the earliest algorithmic artists, using a Zuse Graphomat Z64 plotter2 and ALGOL code to make “something ‘useless’ – geometrical patterns.” In 1969 he made Schotter, a grid of squares, each row slightly more perturbed than the last. It’s clearly digital, but these simple rules create something that looks fluid, like a tattered flag.

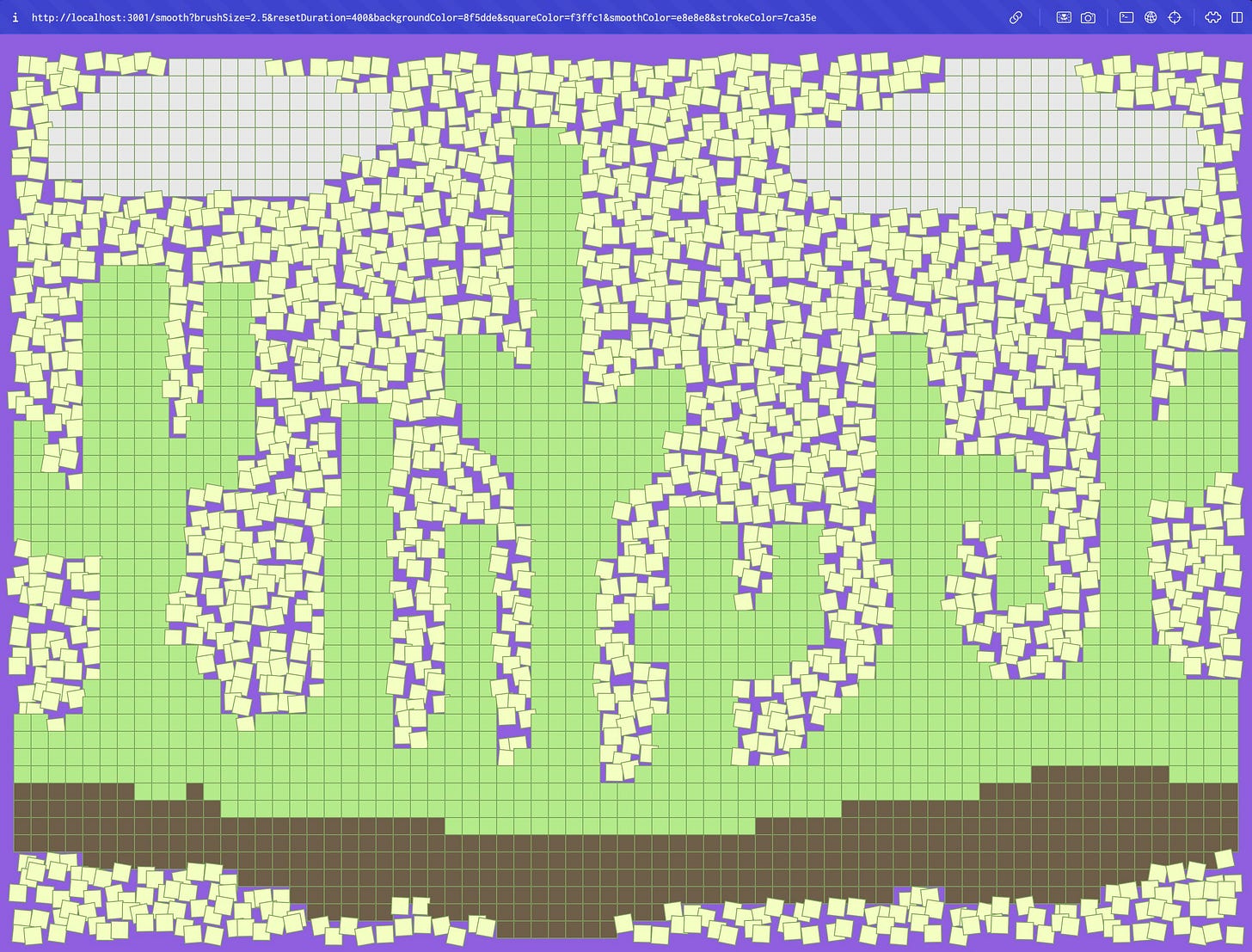

As soon as I saw it, I wanted to recreate it. I had just learned how to use a programming library called d3 to make animated maps, and it felt perfect for this job, so I fired it up and made this — rift:

An earthquake evoked through the same simple rules as Schotter. I’ve watched this disturbance come and go a thousand times. Chaos and order in an endless satisfying cycle.

Disturbance and emergence

Rift sat untouched for years, but every time I’d visit it, I’d have an urge to touch it, to be able to cause a little disturbance in its squares myself.

Years passed and the world transformed. We went from coding by typing precisely ordered symbols to prompting LLMs. What was considered declarative yesterday became the imperative of today and we climbed one more step on the ladder of abstraction. And in this new world, ideas can flow more freely. When AI can do anything, we can use it to fulfill our artistic dreams.

So one week in 2025, inspired, and with Claude by my side, I took the grid of rift, turned off the animation, and made it react to my finger to create a temporary disturbance that smoothed itself out after a moment. This was immediately satisfying. I added color for some life and had disturb, a freeform, calming, ephemeral canvas to draw on.

I got here so quickly I had to keep going. I thought to try something suggested by another early procedural artist, Brian Eno: invert. Instead of starting with order and creating chaos, what if we started with all the squares in disarray and brought them to order?

Thus was born smooth. And once the world was brought back to order, a reward should be earned, so I added an animation: a temporary wave of disturbance.

One animation is great, but when the time between idea and implementation is so small, it’s easy to keep playing, so I added seven more.

Following the desires of the moment can take you to interesting places, and you might find unexpected, unplanned behaviors there. Emergence. This happened in two ways.

First, in smooth: at some point I realized that I could modify the color of the next smoothed square to draw differently colored strokes, and that was enough to turn this fidget toy into a crude drawing app. Cute.

But much more interesting was an emergent property in disturb that came out of a bug in the AI written code.

The animations I made for smooth were fun to watch, and even more fun to trigger at will, so I hooked them up to keyboard shortcuts. When these animations were combined, something totally unexpected happened:

Whoa. I didn’t plan for this. This shouldn’t happen. But one variable was accidentally swapped out for another somewhere deep in the code, so when these waves collided with each other, a whole world of patterns emerged.

These were made with two keystrokes with slightly different timings:

I couldn’t tell you which keystrokes produced these, or how many more patterns are possible:

There are infinities hidden everywhere.

Try it out for yourself: https://shreyans.org/disturb

Hit the buttons to trigger animations. Overlap them. Go wild. See what happens.

Give yourself wings

Everything that happened above could have been made by me, unaided. But I would have had to really want it. It would have taken weeks of evenings to get the animations just right. I would probably have stopped much earlier, and would’ve had to choose between ideas.

Instead, I was able to skate3, and follow that desire, and get to new places, thanks to the tools.

I love great tools. I love the powers they give us. How the right tool makes the execution of the task more enjoyable. How a new tool might make something probable that was previously merely possible, or maybe not even possible. The plotter enabled Nees, tube lights enabled Flavin, paint tubes enabled Monet.

Our newest tool is the collective intelligence of humanity, packaged through decades of math, and delivered through the brilliant orchestration of millions of machines. I see people tripping over themselves to figure out if they should use these tools, if they are good or bad or moral or immoral or human or alien.

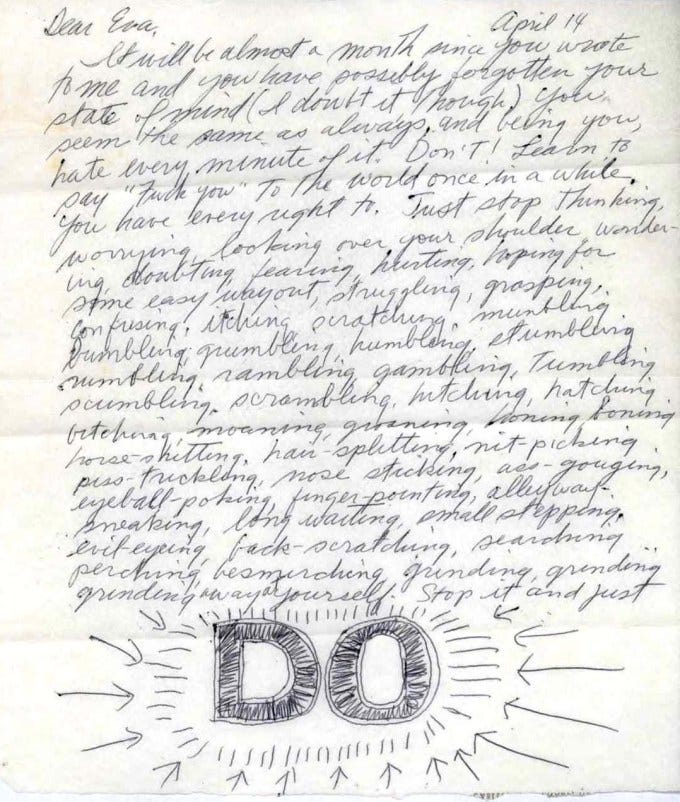

And to that I respond with a letter4 written by Sol LeWitt, who kicked off this story, to a sculptor friend in a creative block:

Just stop thinking, worrying, looking over your shoulder, wondering, doubting, fearing, hurting, hoping for some easy way out, struggling, grasping, confusing, itching, scratching, mumbling, bumbling, grumbling, humbling, stumbling…bitching, moaning, groaning, honing, boning, horse-shitting, hair-splitting, nit-picking…

Stop it and just

→ DO ←

Wishing you a year of experiments and curiosity and threads that you pull into currently unknown places.

Shreyans

January 2, 2026

It’s a time of change, for the world and for me, and it feels like a great time to document the things I’m making and learning. Startups, art, technology, fatherhood, and more. Always hand written, always open minded, usually optimistic. Thanks for reading.

More by and about me at https://shreyans.org, including full screen versions of disturb, smooth, and rift.

https://massmoca.org/event/walldrawing1185/

http://dada.compart-bremen.de/item/device/5

https://www.themarginalian.org/2016/09/09/do-sol-lewitt-eva-hesse-letter/